Government Franchises Course, Form #12.012 (OFFSITE LINK) -SEDM

Forms

Page

Government Franchises Course, Form #12.012 (OFFSITE LINK) -SEDM

Forms

Page

Government Instituted Slavery Using Franchises, Form #05.030 (OFFSITE LINK)-SEDM

Forms

Page

Government Instituted Slavery Using Franchises, Form #05.030 (OFFSITE LINK)-SEDM

Forms

Page

Wikidiff: Franchise v. Privilege (OFFSITE LINK)-franchise and privilege are synonyms

Federal

Jurisdiction, Form #05.018-SEDM

Forms

Page. Section 3 has a detailed explanation of what participating

in federal franchises does to your standing in federal court.

From SEDM Forms Page

Federal

Jurisdiction, Form #05.018-SEDM

Forms

Page. Section 3 has a detailed explanation of what participating

in federal franchises does to your standing in federal court.

From SEDM Forms Page

Why the Federal Income Tax is Limited to Federal Territory, Possessions, Enclaves, Offices, and Other Property, Form #04.404-SEDM

Forms

Page. Use this to prove that income tax may not be offered or enforced within the exclusive jurisdiction of Constitutional States of the Union..

From SEDM Forms Page. This is a Member Subscriber form.

Why the Federal Income Tax is Limited to Federal Territory, Possessions, Enclaves, Offices, and Other Property, Form #04.404-SEDM

Forms

Page. Use this to prove that income tax may not be offered or enforced within the exclusive jurisdiction of Constitutional States of the Union..

From SEDM Forms Page. This is a Member Subscriber form.

Black's Law Dictionary, Fourth Edition, pp. 786-787

FRANCHISE. A special privilege conferred by government on individual or corporation, and which does not belong to citizens of country generally of common right. Elliott v. City of Eugene, 135 Or. 108, 294 P. 358, 360. In England it is defined to be a royal privilege in the hands of a subject.

A "franchise," as used by Blackstone in defining quo warranto, (3 Com. 262 [4th Am. Ed.] 322), had reference to a royal privilege or branch of the king's prerogative subsisting in the hands of the subject, and must arise from the king's grant, or be held by prescription, but today we understand a franchise to be some special privilege conferred by government on an individual, natural or artificial, which is not enjoyed by its citizens in general. State v. Fernandez, 106 Fla. 779, 143 So. 638, 639, 86 A.L.R. 240.

In this country a franchise is a privilege or immunity of a public nature, which cannot be legally exercised without legislative grant. To be a corporation is a franchise. The various powers conferred on corporations are franchises. The execution of a policy of insurance by an insurance company [e.g. Social Insurance/Socialist Security], and the issuing a bank note by an incorporated bank [such as a Federal Reserve NOTE], are franchises. People v. Utica Ins. Co.. 15 Johns., N.Y., 387, 8 Am.Dec. 243. But it does not embrace the property acquired by the exercise of the franchise. Bridgeport v. New York & N. H. R. Co., 36 Conn. 255, 4 Arn.Rep. 63. Nor involve interest in land acquired by grantee. Whitbeck v. Funk, 140 Or. 70, 12 P.2d 1019, 1020. In a popular sense, the political rights of subjects and citizens are franchises, such as the right of suffrage. etc. Pierce v. Emery, 32 N.H. 484 ; State v. Black Diamond Co., 97 Ohio St. 24, 119 N.E. 195, 199, L.R.A.l918E, 352.

Elective Franchise. The right of suffrage: the right or privilege of voting in public elections.

Exclusive Franchise. See Exclusive Privilege or Franchise.

General and Special. The charter of a corporation is its "general" franchise, while a "special" franchise consists in any rights granted by the public to use property for a public use but-with private profit. Lord v. Equitable Life Assur. Soc., 194 N.Y. 212, 81 N. E. 443, 22 L.R.A.,N.S., 420.

Personal Franchise. A franchise of corporate existence, or one which authorizes the formation and existence of a corporation, is sometimes called a "personal" franchise. as distinguished from a "property" franchise, which authorizes a corporation so formed to apply its property to some particular enterprise or exercise some special privilege in its employment, as, for example, to construct and operate a railroad. See Sandham v. Nye, 9 Misc.ReP. 541, 30 N.Y.S. 552.

Secondary Franchises. The franchise of corporate existence being sometimes called the "primary" franchise of a corporation, its "secondary" franchises are the special and peculiar rights, privileges, or grants which it may, receive under its charter or from a municipal corporation, such as the right to use the public streets, exact tolls, collect fares, etc. State v. Topeka Water Co., 61 Kan. 547, 60 P. 337; Virginia Canon Toll Road Co. v. People, 22 Colo. 429, 45 P. 398 37 L.R.A. 711. The franchises of a corporation are divisible into (1) corporate or general franchises; and (2) "special or secondary franchises. The former is the franchise to exist as a corporation, while the latter are certain rights and privileges conferred upon existing corporations. Gulf Refining Co. v. Cleveland Trust Co., 166 Miss. 759, 108 So. 158, 160.

Special Franchisee. See Secondary Franchises, supra.

[Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Edition, pp. 786-787]

What is a Franchises? (OFFSITE LINK) -International Franchise Association

Franchise Rule (OFFSITE LINK) -Federal Trade Commission

Franchise Rule Compliance Guide (OFFSITE LINK) -Federal Trade Commission

People v. Ridgley, 21 Ill. 65, 1859 WL 6687, 11 Peck 65 (Ill., 1859)

“Is it a franchise? A franchise is said to be a right reserved to the people by the constitution, as the elective franchise. Again, it is said to be a privilege conferred by grant from government, and vested in one or more individuals, as a public office. Corporations, or bodies politic are the most usual franchises known to our laws."

[People v. Ridgley, 21 Ill. 65, 1859 WL 6687, 11 Peck 65 (Ill., 1859)]

American Jurisprudence 2d, Franchises, &1: Definitions

“In a legal or narrower sense, the term "franchise" is more often used to designate a right or privilege conferred by law, [1] and the view taken in a number of cases is that to be a franchise, the right possessed must be such as cannot be exercised without the express permission of the sovereign power [2] –that is, a privilege or immunity of a public nature which cannot be legally exercised without legislative grant. [3] It is a privilege conferred by government on an individual or a corporation to do that "which does not belong to the citizens of the country generally by common right." [4] For example, a right to lay rail or pipes, or to string wires or poles along a public street, is not an ordinary use which everyone may make of the streets, but is a special privilege, or franchise, to be granted for the accomplishment of public objects [5] which, except for the grant, would be a trespass. [6] In this connection, the term "franchise" has sometimes been construed as meaning a grant of a right to use public property, or at least the property over which the granting authority has control. [7] ”

[American Jurisprudence 2d, Franchises, §1: Definitions (1999)]___________________________

FOOTNOTES:

[1] People ex rel. Fitz Henry v. Union Gas & E. Co. 254 Ill. 395, 98 N.E. 768; State ex rel. Bradford v. Western Irrigating Canal Co. 40 Kan 96, 19 P. 349; Milhau v. Sharp, 27 N.Y. 611; State ex rel. Williamson v. Garrison (Okla), 348 P.2d. 859; Ex parte Polite, 97 Tex Crim 320, 260 S.W. 1048.

The term "franchise" is generic, covering all the rights granted by the state. Atlantic & G. R. Co. v. Georgia, 98 U.S. 359, 25 L.Ed. 185.

A franchise is a contract with a sovereign authority by which the grantee is licensed to conduct a business of a quasi-governmental nature within a particular area. West Coast Disposal Service, Inc. v. Smith (Fla App), 143 So.2d. 352.[2] The term "franchise" is generic, covering all the rights granted by the state. Atlantic & G. R. Co. v. Georgia, 98 U.S. 359, 25 L.Ed. 185.

A franchise is a contract with a sovereign authority by which the grantee is licensed to conduct a business of a quasi-governmental nature within a particular area. West Coast Disposal Service, Inc. v. Smith (Fla App), 143 So.2d. 352.[3] State v. Real Estate Bank, 5 Ark. 595; Brooks v. State, 3 Boyce (Del) 1, 79 A. 790; Belleville v. Citizens’ Horse R. Co., 152 Ill. 171, 38 N.E. 584; State ex rel. Clapp v. Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co. 40 Minn 213, 41 N.W. 1020.

[4] New Orleans Gaslight Co. v. Louisiana Light & H. P. & Mfg. Co., 115 U.S. 650, 29 L.Ed. 516, 6 S.Ct. 252; People’s Pass. R. Co. v. Memphis City R. Co., 10 Wall (US) 38, 19 L.Ed. 844; Bank of Augusta v. Earle, 13 Pet (U.S.) 519, 10 L.Ed. 274; Bank of California v. San Francisco, 142 Cal. 276, 75 P. 832; Higgins v. Downward, 8 Houst (Del) 227, 14 A. 720, 32 A. 133; State ex rel. Watkins v. Fernandez, 106 Fla. 779, 143 So. 638, 86 A.L.R. 240; Lasher v. People, 183 Ill. 226, 55 N.E. 663; Inland Waterways Co. v. Louisville, 227 Ky. 376, 13 S.W.2d. 283; Lawrence v. Morgan’s L. & T. R. & S. S. Co., 39 La.Ann. 427, 2 So. 69; Johnson v. Consolidated Gas E. L. & P. Co., 187 Md. 454, 50 A.2d. 918, 170 A.L.R. 709; Stoughton v. Baker, 4 Mass 522; Poplar Bluff v. Poplar Bluff Loan & Bldg. Asso., (Mo App) 369 S.W.2d. 764; Madden v. Queens County Jockey Club, 296 N.Y. 249, 72 N.E.2d. 697, 1 A.L.R.2d. 1160, cert den 332 U.S. 761, 92 L.Ed. 346, 68 S.Ct. 63; Shaw v. Asheville, 269 N.C. 90, 152 S.E.2d. 139; Victory Cab Co. v. Charlotte, 234 N.C. 572, 68 S.E.2d. 433; Henry v. Bartlesville Gas & Oil Co., 33 Okla 473, 126 P. 725; Elliott v. Eugene, 135 Or. 108, 294 P. 358; State ex rel. Daniel v. Broad River Power Co. 157 S.C. 1, 153 S.E. 537; State v. Scougal, 3 S.D. 55, 51 N.W. 858; Utah Light & Traction Co. v. Public Serv. Com., 101 Utah 99, 118 P.2d. 683.

A franchise represents the right and privilege of doing that which does not belong to citizens generally, irrespective of whether net profit accruing from the exercise of the right and privilege is retained by the franchise holder or is passed on to a state school or to political subdivisions of the state. State ex rel. Williamson v. Garrison (Okla), 348 P.2d. 859.

Where all persons, including corporations, are prohibited from transacting a banking business unless authorized by law, the claim of a banking corporation to exercise the right to do a banking business is a claim to a franchise. The right of banking under such a restraining act is a privilege or immunity by grant of the legislature, and the exercise of the right is the assertion of a grant from the legislature to exercise that privilege, and consequently it is the usurpation of a franchise unless it can be shown that the privilege has been granted by the legislature. People ex rel. Atty. Gen. v. Utica Ins. Co., 15 Johns (NY) 358.[5] New Orleans Gaslight Co. v. Louisiana Light & H. P. & Mfg. Co., 115 U.S. 650, 29 L.Ed. 516, 6 S.Ct. 252; People’s Pass. R. Co. v. Memphis City R. Co., 10 Wall (US) 38, 19 L.Ed. 844; Bank of Augusta v. Earle, 13 Pet (U.S.) 519, 10 L.Ed. 274; Bank of California v. San Francisco, 142 Cal. 276, 75 P. 832; Higgins v. Downward, 8 Houst (Del) 227, 14 A. 720, 32 A. 133; State ex rel. Watkins v. Fernandez, 106 Fla. 779, 143 So. 638, 86 A.L.R. 240; Lasher v. People, 183 Ill. 226, 55 N.E. 663; Inland Waterways Co. v. Louisville, 227 Ky. 376, 13 S.W.2d. 283; Lawrence v. Morgan’s L. & T. R. & S. S. Co., 39 La.Ann. 427, 2 So. 69; Johnson v. Consolidated Gas E. L. & P. Co., 187 Md. 454, 50 A.2d. 918, 170 A.L.R. 709; Stoughton v. Baker, 4 Mass 522; Poplar Bluff v. Poplar Bluff Loan & Bldg. Asso. (Mo App) 369 S.W.2d. 764; Madden v. Queens County Jockey Club, 296 N.Y. 249, 72 N.E.2d. 697, 1 A.L.R.2d. 1160, cert den 332 U.S. 761, 92 L.Ed. 346, 68 S.Ct. 63; Shaw v. Asheville, 269 N.C. 90, 152 S.E.2d. 139; Victory Cab Co. v. Charlotte, 234 N.C. 572, 68 S.E.2d. 433; Henry v. Bartlesville Gas & Oil Co., 33 Okla 473, 126 P. 725; Elliott v. Eugene, 135 Or. 108, 294 P. 358; State ex rel. Daniel v. Broad River Power Co. 157 S.C. 1, 153 S.E. 537; State v. Scougal, 3 S.D. 55, 51 N.W. 858; Utah Light & Traction Co. v. Public Serv. Com., 101 Utah 99, 118 P.2d. 683.

A franchise represents the right and privilege of doing that which does not belong to citizens generally, irrespective of whether net profit accruing from the exercise of the right and privilege is retained by the franchise holder or is passed on to a state school or to political subdivisions of the state. State ex rel. Williamson v. Garrison (Okla), 348 P.2d. 859.

Where all persons, including corporations, are prohibited from transacting a banking business unless authorized by law, the claim of a banking corporation to exercise the right to do a banking business is a claim to a franchise. The right of banking under such a restraining act is a privilege or immunity by grant of the legislature, and the exercise of the right is the assertion of a grant from the legislature to exercise that privilege, and consequently it is the usurpation of a franchise unless it can be shown that the privilege has been granted by the legislature. People ex rel. Atty. Gen. v. Utica Ins. Co., 15 Johns (NY) 358.[6] People ex rel. Foley v. Stapleton, 98 Colo. 354, 56 P.2d. 931; People ex rel. Central Hudson Gas & E. Co. v. State Tax Com. 247 N.Y. 281, 160 N.E. 371, 57 A.L.R. 374; People v. State Tax Comrs. 174 N.Y. 417, 67 N.E. 69, affd 199 U.S. 1, 50 L.Ed. 65, 25 S.Ct. 705.

[7] Young v. Morehead, 314 Ky. 4, 233 S.W.2d. 978, holding that a contract to sell and deliver gas to a city into its distribution system at its corporate limits was not a franchise within the meaning of a constitutional provision requiring municipalities to advertise the sale of franchises and sell them to the highest bidder.

A contract between a county and a private corporation to construct a water transmission line to supply water to a county park, and giving the corporation the power to distribute water on its own lands, does not constitute a franchise. Brandon v. County of Pinellas (Fla App), 141 So.2d. 278.

U.S. v. Union Pac. R. Co., 98 U.S. 569 (1878)

“The proposition is that the United States, as the grantor of the franchises of the company [a corporation, in this case], the author of its charter, and the donor of lands, rights, and privileges of immense value, and as parens patriae, is a trustee, invested with power to enforce the proper use of the property and franchises granted for the benefit of the public.”

[U.S. v. Union Pac. R. Co., 98 U.S. 569 (1878)][EDITORIAL: "donor of landes, rights, and privileges" implies a loan of government property WITH legislative conditions.]

Black's Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, p. 1269

PARENS PATRIAE. Father of his country; parent of the country. In England, the king. In the United States, the state, as a sovereign-referring to the sovereign power of guardianship over persons under disability; In re Turner, 94 Kan. 115, 145 P. 871, 872, Ann.Cas.1916E, 1022; such as minors, and insane and incompetent persons; McIntosh v. Dill, 86 Okl. 1, 205 P. 917, 925.

[Black’s Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, p. 1269]

U.S. Constitution, Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2

United States Constitution

Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

[EDITORIAL: The franchise codes are the "Rules" above for the loan of the property. This includes the Internal Revenue Code Subtitle A.]

5 U.S.C. 443(a)(2): Rule Making

5 U.S. Code §553 - Rule making

(a) This section applies, according to the provisions thereof, except to the extent that there is involved—

(2) a matter relating to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts.

26 U.S. Code § 7805.Rules and regulations

26 U.S. Code § 7805.Rules and regulations

(a)Authorization

Except where such authority is expressly given by this title to any person other than an officer or employee of the Treasury Department, the Secretary shall prescribe all needful rules and regulations [under Constitution Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2] for the enforcement of this title, including all rules and regulations as may be necessary by reason of any alteration of law in relation to internal revenue.

36 American Jurisprudence 2d, Franchises, §6: As a Contract (1999)

“It is generally conceded that a franchise is the subject of a contract between the grantor and the grantee, and that it does in fact constitute a contract when the requisite element of a consideration is present.[1] Conversely, a franchise granted without consideration is not a contract binding upon the state, franchisee, or pseudo-franchisee.[2] “

[36 American Jurisprudence 2d, Franchises, §6: As a Contract (1999)]_______________________

FOOTNOTES:

1. Larson v. South Dakota, 278 U.S. 429, 73 L.Ed. 441, 49 S.Ct. 196; Grand Trunk Western R. Co. v. South Bend, 227 U.S. 544, 57 L.Ed. 633, 33 S.Ct. 303; Blair v. Chicago, 201 U.S. 400, 50 L.Ed. 801, 26 S.Ct. 427; Arkansas-Missouri Power Co. v. Brown, 176 Ark. 774, 4 S.W.2d. 15, 58 A.L.R. 534; Chicago General R. Co. v. Chicago, 176 Ill. 253, 52 N.E. 880; Louisville v. Louisville Home Tel. Co., 149 Ky. 234, 148 S.W. 13; State ex rel. Kansas City v. East Fifth Street R. Co. 140 Mo. 539, 41 S.W. 955; Baker v. Montana Petroleum Co., 99 Mont. 465, 44 P.2d. 735; Re Board of Fire Comrs. 27 N.J. 192, 142 A.2d. 85; Chrysler Light & P. Co. v. Belfield, 58 N.D. 33, 224 N.W. 871, 63 A.L.R. 1337; Franklin County v. Public Utilities Com., 107 Ohio.St. 442, 140 N.E. 87, 30 A.L.R. 429; State ex rel. Daniel v. Broad River Power Co. 157 S.C. 1, 153 S.E. 537; Rutland Electric Light Co. v. Marble City Electric Light Co., 65 Vt. 377, 26 A. 635; Virginia-Western Power Co. v. Commonwealth, 125 Va. 469, 99 S.E. 723, 9 A.L.R. 1148, cert den 251 U.S. 557, 64 L.Ed. 413, 40 S.Ct. 179, disapproved on other grounds Victoria v. Victoria Ice, Light & Power Co. 134 Va. 134, 114 S.E. 92, 28 A.L.R. 562, and disapproved on other grounds Richmond v. Virginia Ry. & Power Co. 141 Va. 69, 126 S.E. 353.

36 Am.Jur.2d. Franchises from Public Entities, §1

36 Am Jur 2d Franchises from Public Entities § 1

§ 1 DefinitionsA franchise constitutes a private property right. [5]

Similarly stated, a "franchise" is the special privilege awarded by government to a person or corporation and conveys a valuable property right. [6]

To be a "franchise," the right possessed must be such as cannot be exercised without the express permission of the sovereign power. [7]

It is a privilege conferred by the government on an individual or a corporation to do that which does not belong to the citizens of the country generally by common right. [8]

[36 Am.Jur.2d, Franchises from Public Entities §1]____________________________________

FOOTNOTES:

5. Central Waterworks, Inc. v. Town of Century, 754 So.2d. 814 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1st Dist. 2000).

A governmental franchise is deemed to be privately owned, with all of the rights attaching to the ownership of the property in general, and is subject to taxation the same as any other estate in real property. In re South Bay Expressway, L.P., 434 B.R. 589 (Bankr. S.D. Cal. 2010) (applying California law).

6. Montana-Dakota Utilities Co. v. City of Billings, 2003 MT 332, 318 Mont. 407, 80 P.3d 1247 (2003) (holding modified on other grounds by, Havre Daily News, LLC v. City of Havre, 2006 MT 215, 333 Mont. 331, 142 P.3d. 864 (2006)); South Carolina Elec. & Gas Co. v. Town of Awendaw, 359 S.C. 29, 596 S.E.2d. 482 (2004).

A governmental "franchise" constitutes a special privilege granted by the government to particular individuals or companies to be exploited for private profits; such franchisees seek permission to use public streets or rights-of-way in order to do business with a municipality's residents and are willing to pay a fee for this privilege. South Carolina Elec. & Gas Co. v. Town of Awendaw, 359 S.C. 29, 596 S.E.2d. 482 (2004).

8. New Orleans Gas-light Co. v. Louisiana Light & Heat Producing & Manufacturing Co., 115 U.S. 650, 6 S.Ct. 252, 29 L.Ed. 516 (1885); City of Groton v. Yankee Gas Services Co., 224 Conn. 675, 620 A.2d. 771 (1993); Artesian Water Co. v. State, Dept. of Highways and Transp., 330 A.2d. 432 (Del. Super. Ct. 1974), judgment modified on other grounds, 330 A.2d 441 (Del. 1974); City of Poplar Bluff v. Poplar Bluff Loan & Bldg. Ass'n, 369 S.W.2d. 764 (Mo. Ct. App. 1963); Dunmar Inv. Co. v. Northern Natural Gas Co., 185 Neb. 400, 176 N.W.2d. 4 (1970); Petition of South Lakewood Water Co., 61 N.J. 230, 294 A.2d. 13 (1972); Shaw v. City of Asheville, 269 N.C. 90, 152 S.E.2d. 139 (1967); Rural Water Sewer and Solid Waste Management, Dist. No. 1, Logan County, Oklahoma v. City of Guthrie, 2010 OK 51, 2010 WL 2600181 (Okla. 2010); Borough of Scottdale v. National Cable Television, Corp., 28 Pa.Commw. 387, 368 A.2d. 1323 (1977), order aff'd, 476 Pa. 47, 381 A.2d 859 (1977); Quality Towing, Inc. v. City of Myrtle Beach, 345 S.C. 156, 547 S.E.2d. 862 (2001); State/Operating Contractors ABS Emissions, Inc. v. Operating Contractors/State, 985 S.W.2d. 646 (Tex. App. Austin 1999); Tri-County Elec. Ass'n, Inc. v. City of Gillette, 584 P.2d. 995 (Wyo. 1978).

26 C.F.R. § 601.601 - Rules and regulations.

26 C.F.R. §601.601 - Rules and regulations.

§ 601.601 Rules and regulations.

(a) Formulation.

(1) Internal revenue rules take various forms. The most important rules are issued as regulations and Treasury decisions prescribed by the Commissioner and approved by the Secretary or his delegate. Other rules may be issued over the signature of the Commissioner or the signature of any other official to whom authority has been delegated. Regulations and Treasury decisions are prepared in the Office of the Chief Counsel. After approval by the Commissioner, regulations and Treasury decisions are forwarded to the Secretary or his delegate for further consideration and final approval.

20 C.F.R. §422.103(d)

Title 20: Employees' Benefits

PART 422—ORGANIZATION AND PROCEDURES

Subpart B—General Procedures

§422.103 Social security numbers.(d) Social security number cards. A person who is assigned a social security number will receive a social security number card from SSA within a reasonable time after the number has been assigned. (See §422.104 regarding the assignment of social security number cards to aliens.) Social security number cards are the property of SSA and must be returned upon request.

Allstate Insurance Company v. United States, 419 F.2d 409, 415 (Fed. Cir. 1969)

"The Supreme Court, without advancing any precise definition of the term "income tax", has unmistakably determined that taxes imposed on subjects other than income, e.g., franchises, privileges, etc., are not income taxes, although measured on the basis of income. Stratton's Independence, Ltd., v. Howbert, 231 U.S. 399, 34 S. Ct. 136, 58 L.Ed. 285; McCoach v. Minehill S.H.R. Co., 228 U.S. 295, 33 S.Ct. 419, 57 L.Ed. 842; Flint v. Stone Tracy Co., 220 U.S. 107, 31 S. Ct. 342, 55 L.Ed. 389, Ann.Cas. 1912B, 1312; Spreckels Sugar Refining Co. v. McClain, 192 U.S. 397, 24 S.Ct. 376, 48 L.Ed. 496; see: Doyle v. Mitchell Bros. Co., 247 U.S. 179, 183, 38 S.Ct. 467, 62 L.Ed. 1054; United States v. Whitridge, 231 U.S. 144, 147, 34 S.Ct. 24, 58 L.Ed. 159. These criteria are determinative of the nature of the tax in question. [ Id. at 897.]"

[Allstate Insurance Company v. United States, 419 F.2d 409, 415 (Fed. Cir. 1969)]

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288, 56 S.Ct. 466 (1936)

“The principle is invoked that one who accepts the benefit of a statute cannot be heard to question its constitutionality. Great Falls Manufacturing Co. v. Attorney General, 124 U.S. 581, 8 S.Ct. 631, 31 L.Ed. 527; Wall v. Parrot Silver & Copper Co., 244 U.S. 407, 37 S.Ct. 609, 61 L.Ed. 1229; St. Louis, etc., Co., v. George C. Prendergast Const. Co., 260 U.S. 469, 43 S.Ct. 178, 67 L.Ed. 351.”

[Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288, 56 S.Ct. 466 (1936)]

[EDITORIAL: "benefit" is synonymous with PROPERTY, and he who lends property makes all the rules for possessing it. Those rules are the franchise codes themselves.]

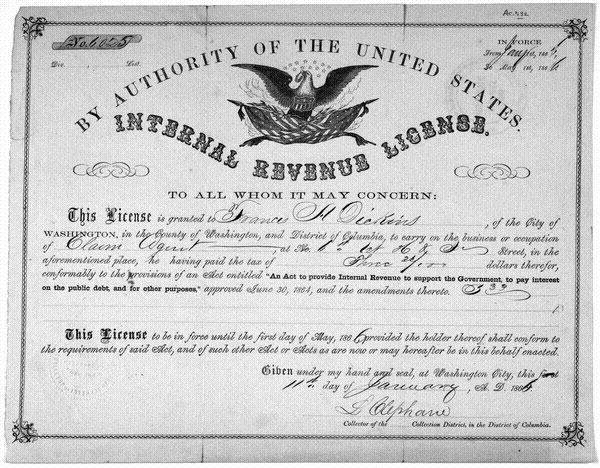

Internal Revenue License,

1866

Does a Lion or Tiger change its stripes?

This could be a license for liquor or firearms…but the generic words “carry on the business or occupation” of this 1866 Internal Revenue License bear striking generality to the generic words “trade or business” of the present IRS scam.

Notice the act to provide “Internal Revenue to support the government…”

Notice this very early license is for Washington DC.

[Comment: Whenever one sees United States in law or government form, it usually applies just to Exclusive Legislation areas.]

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/rbpe:@field(DOCID+@lit(rbpe20506800))

Text:

[By authority of the United States. Internal revenue licence ... Collection district in the District of Columbia. [Washington D. C. 1869].

License Tax Cases, 72 U.S. 462, 18 L.Ed. 497, 5 Wall. 462, 2 A.F.T.R. 2224 (1866)

"Thus, Congress having power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes, may, without doubt, provide for granting coasting licenses, licenses to pilots, licenses to trade with the Indians, and any other licenses necessary or proper for the exercise of that great and extensive power; and the same observation is applicable to every other power of Congress, to the exercise of which the granting of licenses may be incident. All such licenses confer authority, and give rights to the licensee. But very different considerations apply to the internal commerce or domestic trade of the States. Over this commerce and trade Congress has no power of regulation nor any direct control. This power belongs exclusively to the States. No interference by Congress with the business of citizens transacted within a State is warranted by the Constitution, except such as is strictly incidental to the exercise of powers clearly granted to the legislature. The power to authorize [e.g. "LICENSE"] a business within a State is plainly repugnant to the exclusive power of the State over the same subject. It is true that the power of Congress to tax is a very extensive power. It is given in the Constitution, with only one exception and only two qualifications. Congress cannot tax exports, and it must impose direct taxes by the rule of apportionment, and indirect taxes by the rule of uniformity. Thus limited, and thus only, it reaches every subject, and may be exercised at discretion. But, it reaches only existing subjects. Congress cannot authorize [e.g. LICENSE] a trade or business within a State in order to tax it."

[License Tax Cases, 72 U.S. 462, 18 L.Ed. 497, 5 Wall. 462, 2 A.F.T.R. 2224 (1866)]

In re Meador, 1 Abb.U.S.

317, 16 F.Cas. 1294, D.C.Ga.

(1869)

In re Meador, 1 Abb.U.S.

317, 16 F.Cas. 1294, D.C.Ga.

(1869)

"And here a thought suggests itself. As the Meadors, subsequently to the passage of this act of July 20, 1868, applied for and obtained from the government a license or permit to deal in manufactured tobacco, snuff and cigars, I am inclined to be of the opinion that they are, by this their own voluntary act, precluded from assailing the constitutionality of this law, or otherwise controverting it. For the granting of a license or permit-the yielding of a particular privilege-and its acceptance by the Meadors, was a contract, in which it was implied that the provisions of the statute which governed, or in any way affected their business, and all other statutes previously passed, which were in pari materia with those provisions, should be recognized and obeyed by them. When the Meadors sought and accepted the privilege, the law was before them. And can they now impugn its constitutionality or refuse to obey its provisions and stipulations, and so exempt themselves from the consequences of their own acts?

whether they were in conflict with any of the provisions of the constitution. My conclusion on that question has been expressed. I do not concur with counsel, that these laws are unreasonably burdensome. But even if they are, nay, even if they are oppressive, and unjust modes are employed for their enforcement, the remedy lies with congress, and not with the judiciary. By enacting these laws congress has exercised the constitutional power of taxation, and the courts have no power to interfere. Providence Bank v. Billings, 4 Pet. [29 U. S.] 514; Extension of Hancock Street, 18 Pa. St. 26; Kirby v. Shaw, 19 Pa. St. 258; Livingston v. Mayor, etc., of New York, 8 Wend. 85; In re Opening Furman Street, 17 Wend. 649; Herrick v. Randolph, 13 Vt. 525. In McCulloch v. State of Maryland, 4 Wheat. [17 U. S.] 316, 430, Chief Justice Marshall said, that it was unfit for the judicial department to ‘inquire what degree of taxation is the legitimate use, and what degree may amount to the abuse of the power.’ [

In re Meador, Abb.U.S. 317, 16 F.Cas. 1294, D.C.Ga. (1869)]

People v. Ridgley, 21 Ill. 65, 1859 WL 6687, 11 Peck 65 (Ill., 1859)

“Is it a franchise? A franchise is said to be a right reserved to the people by the constitution, as the elective franchise. Again, it is said to be a privilege conferred by grant from government, and vested in one or more individuals, as a public office. Corporations, or bodies politic are the most usual franchises known to our laws. In England they are very numerous, and are defined to be royal privileges in the hands of a subject. An information will lie in many cases growing out of these grants, especially where corporations are concerned, as by the statute of 9 Anne, ch. 20, and in which the public have an interest. In 1 Strange R. ( The King v. Sir William Louther,) it was held that an information of this kind did not lie in the case of private rights, where no franchise of the crown has been invaded.

If this is so--if in England a privilege existing in a subject, which the king alone could grant, constitutes it a franchise--in this country, under our institutions, a privilege or immunity of a public nature, which could not be exercised without a legislative grant, would also be a franchise.”

[People v. Ridgley, 21 Ill. 65, 1859 WL 6687, 11 Peck 65 (Ill., 1859)]

U.S. v. Union Pac. R. Co., 98 U.S. 569 (1878)

U.S. v. Union Pac. R. Co., 98 U.S. 569 (1878)

The question for decision is, therefore, squarely presented to us, as it was to the Circuit Court, whether, by the aid of that statute, and within the limits of the power it intended to confer, this bill can be sustained under the general principles of equity jurisprudence.

We say by the aid of that statute, because it is conceded on all sides that without it the bill cannot stand. The service of compulsory process on a party residing without the limits of the district of Connecticut who is not found within them, is expressly forbidden by the general statute defining the jurisdiction of the circuit courts. Parties and subjects of complaint having no proper connection with each other are grouped *602 together in this bill, and they, by the accepted canons of equity, pleading, render it multifarious. This, and other matters of like character, which are proper causes of demurrer, are fatal to it, unless the difficulty be cured by the statute.

When we recur to its provisions, which are said to authorize these and other departures from the general rules of equity procedure, counsel for the appellees insist that it is unconstitutional, not only in the particulars just alluded to, but that it is absolutely void as affecting the substantial rights of defendants in regard to matters beyond the power of Congress.

If this be true, we need inquire no further into the frame of the bill, and we therefore proceed, on the threshold, to consider the objections to the validity of the statute.

The Constitution declares (art. 3, sect. 2) that the judicial power shall extend to all cases in law and equity arising under the Constitution, the laws of the United States, and the treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority; and to controversies to which the United States shall be a party.

>**26 The matters in regard to which the statute authorizes a suit to be brought are very largely those arising under the act which chartered the Union Pacific Railroad Company, conferred on it certain rights and benefits, and imposed on it certain obligations. It is in reference to these rights and obligations that the suit is to be brought. It is also be be brought by the United States, which is, therefore, necessarily the party complainant. Whether, therefore, this suit is authorized by the statute or not, it is very clear that the general subject on which Congress legislated is within the judicial power as defined by the Constitution.

The same article declares, in sect. 1, that this ‘power shall be vested in one supreme court and in such inferior courts as the Congress may, from time to time, ordain.’

The discretion, therefore, of Congress as to the number, the character, the territorial limits of the courts among which it shall distribute this judicial power, is unrestricted except as to the Supreme Court. On that court the same article of the Constitution confers a very limited original jurisdiction,-namely, ‘in all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers, and consuls, and cases in which a State shall be a party,’-and an *603 appellate jurisdiction in all the other cases to which this judicial power extends, with such exceptions and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.

There is in this same section a limitation as to the place of trial of all crimes, which it declares shall (except in cases of impeachment) be held in the State where they shall have been committed, if committed within any State.

Article 6 of the amendments also provides that in all criminal prosecutions ‘the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law.’ These provisions, which relate solely to the place of the trial for criminal offences, do not affect the general proposition. We say, therefore, that, with the exception of the Supreme Court, the authority of Congress, in creating courts and conferring on them all or much or little of the judicial power of the United States, is unlimited by the Constitution.

Congress has, under this authority, created the district courts, the circuit courts, and the Court of Claims, and vested each of them with a defined portion of the judicial power found in the Constitution. It has also regulated the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and the Court of Claims is not confined by geographical boundaries. Each of them, having by the law of its organization jurisdiction of the subject-matter of a suit, and of the parties thereto, can, sitting at Washington, exercise its power by appropriate process, served anywhere within the limits of the territory over which the Federal government exercises dominion.

**27 It would have been competent for Congress to organize a judicial system analogous to that of England and of some of the States of the Union, and confer all original jurisdiction on a court or courts which should possess the judicial power with which that body thought proper, within the Constitution, to invest them, with authority to exercise that jurisdiction throughout the limits of the Federal government. This has been done in reference to the Court of Claims. It has now jurisdiction only of cases in which the United States is defendant. It is just as *604 clearly within the power of Congress to give it exclusive jurisdiction of all actions in which the United States is plaintiff. Such an extension of its jurisdiction would include all that the statute under consideration has granted to the Circuit Court.

It is true that Congress has declared that no person shall be sued in a circuit court of the United States who does not reside within the district for which the court was established, or who is not found there. But a citizen residing in Oregon may be sued in Maine, if found there, so that process can be served on him. There is, therefore, nothing in the Constitution which forbids Congress to enact that, as to a class of cases or a case of special character, a circuit court-any circuit court-in which the suit may be brought, shall, by process served anywhere in the United States, have the power to bring before it all the parties necessary to its decision.

Whether parties shall be compelled to answer in a court of the United States wherever they may be served, or shall only be bound to appear when found within the district where the suit has been brought, is merely a matter of legislative discretion, which ought to be governed by considerations of conveyience, expense, &c., but which, when exercised by Congress, is controlling on the courts.

So, also, the doctrine of multifariousness; whether relating to improperly combining persons or grievances in the bill, it is simply a rule of pleading adopted by courts of equity. It has been found convenient in the administration of justice, and promotive of that end, that parties who have no proper connection with each other shall not be compelled to litigate together in the same suit, and that matters wholly distinct from and having no relation to each other, and requiring defences equally unconnected, shall not be alleged and determined in one suit. The rule itself, however, is a very accommodating one, and by no means inflexible. Such as it is, however, it may be modified, limited, and controlled by the same power which creates the court and confers its jurisdiction. The Constitution imposes no restraint in this respect upon the power of Congress. Sect. 921 of the Revised Statutes, which has been the law for fifty years, declares that when causes of like nature or relating to the same question are pending, the court may consolidate *605 them, or make such other orders as are necessary to avoid costs and delay. It is every-day practice, under this rule, to do what the statute authorizes to be done in the case before us.

**28 But it is argued that the statute confers a special jurisdiction to try a single case, and is intended to grant the complainant new and substantial rights, at the expense and by a corresponding invasion of those of the defendants.

It does not create a new or special tribunal. Any circuit court of the United States where the bill might be filed was, by the act, invested with the jurisdiction to try the case. Nor was new power conferred on the court beyond those which we have regarded as affecting the mode of procedure. It seems to us that any circuit court, sitting as a court of equity, which could by its process have lawfully obtained jurisdiction of the parties, and considered in one suit all the matters mentioned in the statute, could have done this before the act as well as afterwards.

But if this be otherwise, we are aware of no constitutional objection to the power of the legislative body to confer on an existing court a special jurisdiction to try a specific matter which in its nature is of judicial cognizance.

The principal defendant in this suit, the one around which all the contest is ranged, is a corporation created by an act which reserved the right of Congress to repeal or modify the charter. To this corporation Congress made a loan of $27,000,000, and a donation of lands of a value probably equal to the loan.

The statute-books of the States are full of acts directing the law officers to proceed against corporations, such as banks, insurance companies, and others, in order to have a decree declaring their charters forfeited. Special statutes are also common, ordering suits against such corporations when they have become insolvent, to wind up their business affairs, and to distribute their assets, and prescribing with minuteness the course of procedure which shall be followed and the court in which the suit shall be brought.

This court said, in the case of The Bank of Columbia v. Okely (4 Wheat. 235), in speaking of a summary proceeding given by the charter of that bank for the collection of its debts: ‘It is the remedy, and not the right, and as such we have no doubt *606 of its being subject to the will of Congress. The forms of administering justice, and the duties and powers of courts as incident to the exercise of a branch of sovereign power, must ever be subject to legislative will, and the power over them is unalienable, so as to bind subsequent legislatures.’ And in Young v. The Bank of Alexandria (4 Cranch, 397), Mr. Chief Justice Marshall says: ‘There is a difference between those rights on which the validity of the transactions of the corporation depends, which must adhere to those transactions everywhere, and those peculiar remedies which may be bestowed on it. The first are of general obligation; the last, from their nature, can only be exercised in those courts which the power making the grant can regulate.’ See also The Commonwealth v. The Delaware & Hudson Canal Co. et al., 43 Pa. St. 227; State of Maryland v. Northern Central Railroad Co., 18 Md. 193; Colby v. Dennis, 36 Me. 1; Gowan v. Penobscot Railroad Co., 44 id. 140.

**29 Statutes of this character, if not so common as to be called ordinary legislation, are yet frequent enough to justify us in saying that they are well-recognized acts of legislative power uniformly sustained by the courts.

It may be said, and probably with truth, that such statutes, when they have been held to be valid by the courts, do not infringe the substantial rights of property or of contract of the parties affected, but are intended to supply defects of power in the courts, or to give them improved methods of procedure in dealing with existing rights.

This leads to an inquiry indispensable to a sound decision of the case before us; namely, does this statute, by its true construction, do any thing more than this?

We might rest this branch of the case upon the concession of counsel for appellants, made both in their brief and in the oral argument, but we proceed to examine the proposition for ourselves.

The first suggestion of the legal mind on this inquiry is, that it will not be presumed, unless the language of the statute imperatively requires it, that Congress, by a retrospective law, intended to create new rights in one party to the suit at the expense, or by an invasion of the rights, of other parties; or, *607 where no right of action founded on past transactions existed, that Congress intended to create it.

The United States was to be sole complainant in a suit in equity, and though there may be other defendants, the Union Pacific Railroad Company is the only one named in the act. The relief to be granted is the collection and payment of moneys and the restoration of property, or its value, ‘either to said railroad corporation or to the United States, whichever shall in equity be entitled thereto.’ The decree, therefore, can only be made on the ground of some relief to which the United States or the company is entitled by the general principles of equity jurisprudence. It is no objection to granting such relief that the company is a defendant, for by the flexibility of chancery practice a person whose interests in the subject of litigation are on the same side with the complainant may be made a defendant. The corporation could also in such a suit file a cross-bill against the complainant, and, by virtue of this statute, against any co-defendant of whom it could rightfully claim the relief which the statute authorizes.But whatever be the relief asked, it could only, by the express terms of the act, be granted to that party who was in equity thereunto entitled. It is very plain that there was here no new right established. No new cause of equitable relief. No new rule for determining what were the rights of the parties. That was to be decided by the principles of equity; not new principles of equity, but the existing principles of equitable jurisprudence.

But the statute very specifically defines the matters which may be embraced in this suit as foundations for relief, and classifies them under a very few heads, by declaring who besides the corporation may be sued. They are persons who have received,--

[. . .]The proposition is that the United States, as the grantor of the franchises of the company, the author of its charter, and the donor of lands, rights, and privileges of immense value, and as parens patriae, is a trustee, invested with power to enforce the proper use of the property and franchises granted for the benefit of the public.

The legislative power of Congress over this subject has already been considered, and need not be further alluded to. The trust here relied on is one which is supposed to grow out of the relations of the corporation to the government, which, without any aid from legislation, are cognizable in the ordinary courts of equity.

It must be confessed that, with every desire to find some clear and well-defined statement of the foundation for relief under this head of jurisdiction, and after a very careful examination of the authorities cited, the nature of this claim of right remains exceedingly vague. Nearly all the cases- we may almost venture to say all of them-fall under two heads:--

1. Where municipal, charitable, religious, or eleemosynary corporations, public in their character, had abused their franchises, perverted the purpose of their organization, or misappropriated their funds, and as they, from the nature of their corporate functions, were more or less under government supervision, the Attorney-General proceeded against them to obtain correction of the abuse; or,

2. Where private corporations, chartered for definite and limited purposes, had exceeded their powers, and were restrained *618 or enjoined in the same manner from the further violation of the limitation to which their powers were subject.

The doctrine in this respect is well condensed in the opinion in The People v. Ingersoll, recently decided by the Court of Appeals of New York. 58 N. Y. 1. ‘If,’ says the court, ‘the property of a corporation be illegally interfered with by corporation officers and agents or others, the remedy is by action at the suit of the corporation, and not of the Attorney-General. Decisions are cited from the reports of this country and of this State, entitled to consideration and respect, affirming to some extent the doctrine of the English courts, and applying it to like cases as they have arisen here. But in none has the doctrine been extended beyond the principles of the English cases; and, aside from the jurisdiction of courts of equity over trusts of property for public uses and over the trustees, either corporate or official, the courts have only interfered at the instance of the Attorney-General to prevent and prohibit some official wrong by municipal corporations or public officers, and the exercise of usurped or the abuse of actual powers.’ p. 16.

**37 To bring the present case within the rule governing the exercise of the equity powers of the court, it is strongly urged that the company belongs to the class first described.

The duties imposed upon it by the law of its creation, the loan of money and the donation of lands made to it by the United States, its obligation to carry for the government, and the great purpose of Congress in opening a highway for public use and the postal service between the widely separated States of the Union, are relied on as establishing this proposition.

But in answer to this it must be said that, after all, it is but a railroad company, with the ordinary powers of such corporations. Under its contract with the government, the latter has taken good care of itself; and its rights may be judicially enforced without the aid of this trust relation. They may be aided by the general legislative powers of Congress, and by those reserved in the charter, which we have specifically quoted.

The statute which conferred the benefits on this company, the loan of money, the grant of lands, and the right of way, did the same for other corporations already in existence under State or territorial charters. Has the United States the right *619 to assert a trust in the Federal government which would authorize a suit like this by the Attorney-General against the Kansas Pacific Railway Company, the Central Pacific Railroad Company, and other companies in a similar position?

If the United States is a trustee, there must be cestuis que trust. There cannot be the one without the other, and the trustee cannot be a trustee for himself alone. A trust does not exist when the legal right and the use are in the same party, and there are no ulterior trusts.

Who are the cestuis que trust for whose benefit this suit is brought? If they be the defrauded stockholders, we have already shown that they are capable of asserting their own rights; that no provision is made for securing them in this suit should it be successful, and that the statute indicates no such purpose.

If the trust concerned relates to the rights of the public in the use of the road, no wrong is alleged capable of redress in this suit, or which requires such a suit for redress.

Railroad Company v. Peniston (18 Wall. 5) shows that the company is not a mere creature of the United States, but that while it owes duties to the government, the performance of which may, in a proper case, be enforced, it is still a private corporation, the same as other railroad companies, and, like them, subject to the laws of taxation and the other laws of the States in which the road lies, so far as they do not destroy its usefulness as an instrument for government purposes.

We are not prepared to say that there are no trusts which the United States may not enforce in a court of equity against this company. When such a trust is shown, it will be time enough to recognize it. But we are of opinion that there is none set forth in this bill which, under the statute authorizing the present suit, can be enforced in the Circuit Court.

**38 There are many matters alleged in the bill in this case, and many points ably presented in argument, which have received our careful attention, but of which we can take no special notice in this opinion. We have devoted so much space to the more important matters, that we can only say that, under the view which we take of the scope of the enabling statute, they furnish no ground for relief in this suit.

*620 The liberal manner in which the government has aided this company in money and lands is much urged upon us as a reason why the rights of the United States should be liberally construed. This matter is fully considered in the opinion of the court already cited, in United States v. Union Pacific Railroad Co. (supra), in which it is shown that it was a wise liberality for which the government has received all the advantages for which it bargained, and more than it expected. In the feeble infancy of this child of its creation, when its life and usefulness were very uncertain, the government, fully alive to its importance, did all that it could to strengthen, support, and sustain it. Since it has grown to a vigorous manhood, it may not have displayed the gratitude which so much care called for. If this be so, it is but another instance of the absence of human affections which is said to characterize all corporations. It must, however, be admitted that it has fulfilled the purpose of its creation and realized the hopes which were then cherished, and that the government has found it a useful agent, enabling it to save vast sums of money in the transportation of troops, mails, and supplies, and in the use of the telegraph.

A court of justice is called on to inquire not into the balance of benefits and favors on each side of this controversy, but into the rights of the parties as established by law, as found in their contracts, as recognized by the settled principles of equity, and to decide accordingly. Governed by this rule, and by the intention of the legislature in passing the act under which this suit is brought, we concur with the Circuit Court in holding that no case for relief is made by the bill.

[U.S. v. Union Pac. R. Co., 98 U.S. 569 (1878)]

SEDM Disclaimer, Section 4: Meaning of Words

4.10. Franchise

The word "franchise" means a grant or rental or lease rather than a gift of specific property with legal strings or "obligations" attached.

FRANCHISE. A special privilege conferred by government on individual or corporation, and which does not belong to citizens of country generally of common right. Elliott v. City of Eugene, 135 Or. 108, 294 P. 358, 360. In England it is defined to be a royal privilege in the hands of a subject.

A "franchise," as used by Blackstone in defining quo warranto, (3 Com. 262 [4th Am. Ed.] 322), had reference to a royal privilege or branch of the king's prerogative subsisting in the hands of the subject, and must arise from the king's grant, or be held by prescription, but today we understand a franchise to be some special privilege conferred by government on an individual, natural or artificial, which is not enjoyed by its citizens in general. State v. Fernandez, 106 Fla. 779, 143 So. 638, 639, 86 A.L.R. 240.

In this country a franchise is a privilege or immunity of a public nature, which cannot be legally exercised without legislative grant. To be a corporation is a franchise. The various powers conferred on corporations are franchises. The execution of a policy of insurance by an insurance company [e.g. Social Insurance/Socialist Security], and the issuing a bank note by an incorporated bank [such as a Federal Reserve NOTE], are franchises. People v. Utica Ins. Co.. 15 Johns., N.Y., 387, 8 Am.Dec. 243. But it does not embrace the property acquired by the exercise of the franchise. Bridgeport v. New York & N. H. R. Co., 36 Conn. 255, 4 Arn.Rep. 63. Nor involve interest in land acquired by grantee. Whitbeck v. Funk, 140 Or. 70, 12 P.2d 1019, 1020. In a popular sense, the political rights of subjects and citizens are franchises, such as the right of suffrage. etc. Pierce v. Emery, 32 N.H. 484 ; State v. Black Diamond Co., 97 Ohio St. 24, 119 N.E. 195, 199, L.R.A.l918E, 352.

Elective Franchise. The right of suffrage: the right or privilege of voting in public elections.

Exclusive Franchise. See Exclusive Privilege or Franchise.

General and Special. The charter of a corporation is its "general" franchise, while a "special" franchise consists in any rights granted by the public to use property for a public use but-with private profit. Lord v. Equitable Life Assur. Soc., 194 N.Y. 212, 81 N. E. 443, 22 L.R.A.,N.S., 420.

Personal Franchise. A franchise of corporate existence, or one which authorizes the formation and existence of a corporation, is sometimes called a "personal" franchise. as distinguished from a "property" franchise, which authorizes a corporation so formed to apply its property to some particular enterprise or exercise some special privilege in its employment, as, for example, to construct and operate a railroad. See Sandham v. Nye, 9 Misc.ReP. 541, 30 N.Y.S. 552.

Secondary Franchises. The franchise of corporate existence being sometimes called the "primary" franchise of a corporation, its "secondary" franchises are the special and peculiar rights, privileges, or grants which it may, receive under its charter or from a municipal corporation, such as the right to use the public streets, exact tolls, collect fares, etc. State v. Topeka Water Co., 61 Kan. 547, 60 P. 337; Virginia Canon Toll Road Co. v. People, 22 Colo. 429, 45 P. 398 37 L.R.A. 711. The franchises of a corporation are divisible into (1) corporate or general franchises; and (2) "special or secondary franchises. The former is the franchise to exist as a corporation, while the latter are certain rights and privileges conferred upon existing corporations. Gulf Refining Co. v. Cleveland Trust Co., 166 Miss. 759, 108 So. 158, 160.

Special Franchisee. See Secondary Franchises, supra.

[Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Edition, pp. 786-787]

The definition of "privilege" in the definition above means PROPERTY, whether physical or intangible. This loan is often called a "grant" in statutes, as in the case of Social Security in 42 U.S. Code Subchapter I-Grants to the States for Old-Age Assistance. That grant is to federal territories and NOT constitutional states, as demonstrated by the definition of "State" found in 42 U.S.C. §1301(a)(1). Hence, Social Security cannot be offered in constitutional states, but only federal territories, as proven in Form #06.001.

"For here, the state must deposit the proceeds of its taxation in the federal treasury, upon terms which make the deposit suspiciously like a forced loan to be repaid only in accordance with restrictions imposed by federal law. Title IX, §§ 903 (a) (3), 904 (a), (b), (e). All moneys withdrawn from this fund must be used exclusively for the payment of compensation. § 903 (a) (4). And this compensation is to be paid through public employment offices in the state or such other agencies as a federal board may approve. § 903 (a) (1)."

[Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548 (1937)]In the case of government franchises, property granted or rented can include one or more of the following:

- A public right or public privilege granted by a statute that is not found in the Constitution but rather created by the Legislature. This includes remedies provided in franchise courts in the Executive Branch under Ariticle I or Article IV to vindicate such rights. It does not include remedies provided in true Article III courts.

“The distinction between public rights and private rights has not been definitively explained in our precedents. Nor is it necessary to do so in the present cases, for it suffices to observe that a matter of public rights must at a minimum arise “between the government and others.” Ex parte Bakelite Corp., supra, at 451, 49 S.Ct., at 413. In contrast, “the liability of one individual to another under the law as defined,” Crowell v. Benson, supra, at 51, 52 S.Ct., at 292, is a matter of private rights. Our precedents clearly establish that only controversies in the former category may be removed from Art. III courts and delegated to legislative courts or administrative agencies for their determination. See Atlas Roofing Co. v. Occupational Safety and Health Review Comm'n, 430 U.S. 442, 450, n. 7, 97 S.Ct. 1261, 1266, n. 7, 51 L.Ed.2d. 464 (1977); Crowell v. Benson, supra, 285 U.S., at 50-51, 52 S.Ct., at 292. See also Katz, Federal Legislative Courts, 43 Harv.L.Rev. 894, 917-918 (1930).FN24 Private-rights disputes, on the other hand, lie at the core of the historically recognized judicial power.”

[. . .]

Although Crowell and Raddatz do not explicitly distinguish between rights created by Congress [PUBLIC RIGHTS] and other [PRIVATE] rights, such a distinction underlies in part Crowell's and Raddatz' recognition of a critical difference between rights created by federal statute and rights recognized by the Constitution. Moreover, such a distinction seems to us to be necessary in light of the delicate accommodations required by the principle of separation of powers reflected in Art. III. The constitutional system of checks and balances is designed to guard against “encroachment or aggrandizement” by Congress at the expense of the other branches of government. Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S., at 122, 96 S.Ct., at 683. But when Congress creates a statutory right [a “privilege” or “public right” in this case, such as a “trade or business”], it clearly has the discretion, in defining that right, to create presumptions, or assign burdens of proof, or prescribe remedies; it may also provide that persons seeking to vindicate that right must do so before particularized tribunals created to perform the specialized adjudicative tasks related to that right. FN35 Such provisions do, in a sense, affect the exercise of judicial power, but they are also incidental to Congress' power to define the right that it has created. No comparable justification exists, however, when the right being adjudicated is not of congressional creation. In such a situation, substantial inroads into functions that have traditionally been performed by the Judiciary cannot be characterized merely as incidental extensions of Congress' power to define rights that it has created. Rather, such inroads suggest unwarranted encroachments upon the judicial power of the United States, which our Constitution reserves for Art. III courts.

[Northern Pipeline Const. Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co., 458 U.S. 50, 102 S.Ct. 2858 (1983)]- Any type of privilege, immunity, or exemption granted by a statute to a specific class of people and not to all people generally that is not found in the Constitution. All such statues are referred to as "special law" or "private law", where the government itself is acting in a private rather than a public capacity on an equal footing with every other private human in equity. The U.S. Supreme court also called such legislation "class legislation" in Pollock v. Farmers Loan and Trust, 157 U.S. 429 (1895) and the ONLY "class" they can be talking about are public officers in the U.S. government and not to all people generally. See Why Your Government is Either a Thief or You are a "Public Officer" For Income Tax Purposes, Form #05.008 for proof:

“special law. One relating to particular persons or things; one made for individual cases or for particular places or districts; one operating upon a selected class, rather than upon the public generally. A private law. A law is "special" when it is different from others of the same general kind or designed for a particular purpose, or limited in range or confined to a prescribed field of action or operation. A "special law" relates to either particular persons, places, or things or to persons, places, or things which, though not particularized, are separated by any method of selection from the whole class to which the law might, but not such legislation, be applied. Utah Farm Bureau Ins. Co. v. Utah Ins. Guaranty Ass'n, Utah, 564 P.2d. 751, 754. A special law applies only to an individual or a number of individuals out of a single class similarly situated and affected, or to a special locality. Board of County Com'rs of Lemhi County v. Swensen, Idaho, 80 Idaho 198, 327 P.2d. 361, 362. See also Private bill; Private law. Compare General law; Public law.”

[Black’s Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, pp. 1397-1398]- A statutory "civil status" created and therefore owned by the legislature. This includes statutory "taxpayers", "drivers", "persons", "individuals", etc. All such entities are creations of Congress and public rIghts which carry obligations when consensually and lawfully exercised. See:

Your Exclusive Right to Declare or Establish Your Civil Status, Form #13.008- A STATUTORY Social Security Card. The regulations at 20 C.F.R. §422.103(d) indicates the card is property of the government and must be returned upon request.

- A U.S. passport. The passport indicates that it is property of the government that must be returned upon request.

- A "license", which is legally defined as permission by the state to do something that would otherwise be illegal or even criminal.

In legal parlance, such a grant makes the recipient a temporary trustee, and if they violate their trust, the property can be taken back through administrative action or physical seizure and without legal process so long as the conditions of the loan allowed for these methods of enforcement:

“How, then, are purely equitable obligations created? For the most part, either by the acts of third persons or by equity alone. But how can one person impose an obligation upon another? By giving property to the latter on the terms of his assuming an obligation in respect to it. At law there are only two means by which the object of the donor could be at all accomplished, consistently with the entire ownership of the property passing to the donee, namely: first, by imposing a real obligation upon the property; secondly, by subjecting the title of the donee to a condition subsequent. The first of these the law does not permit; the second is entirely inadequate. Equity, however, can secure most of the objects of the doner, and yet avoid the mischiefs of real obligations by imposing upon the donee (and upon all persons to whom the property shall afterwards come without value or with notice) a personal obligation with respect to the property; and accordingly this is what equity does. It is in this way that all trusts are created, and all equitable charges made (i.e., equitable hypothecations or liens created) by testators in their wills. In this way, also, most trusts are created by acts inter vivos, except in those cases in which the trustee incurs a legal as well as an equitable obligation. In short, as property is the subject of every equitable obligation, so the owner of property is the only person whose act or acts can be the means of creating an obligation in respect to that property. Moreover, the owner of property can create an obligation in respect to it in only two ways: first, by incurring the obligation himself, in which case he commonly also incurs a legal obligation; secondly, by imposing the obligation upon some third person; and this he does in the way just explained.”

[Readings on the History and System of the Common Law, Second Edition, Roscoe Pound, 1925, p. 543]__________________________________________________

“When Sir Matthew Hale, and the sages of the law in his day, spoke of property as affected by a public interest, and ceasing from that cause to be juris privati solely, that is, ceasing to be held merely in private right, they referred to

[1] property dedicated [DONATED] by the owner to public uses, or

[2] to property the use of which was granted by the government [e.g. Social Security Card], or

[3] in connection with which special privileges were conferred [licenses].

Unless the property was thus dedicated [by one of the above three mechanisms], or some right bestowed by the government was held with the property, either by specific grant or by prescription of so long a time as to imply a grant originally, the property was not affected by any public interest so as to be taken out of the category of property held in private right.”

[Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113, 139-140 (1876)]The above authorities imply that a mere act of accepting or using the property in question in effect represents "implied consent" to abide by the conditions associated with the loan, as described in the California Civil Code below:

CALIFORNIA CIVIL CODE

DIVISION 3. OBLIGATIONS

PART 2. CONTRACTS

CHAPTER 3. CONSENT

Section 15891589. A voluntary acceptance of the benefit of a transaction is equivalent to a consent to all the obligations arising from it, so far as the facts are known, or ought to be known, to the person accepting.

The U.S. Supreme Court further acknowledged the above mechanisms of using grants or loans of government property to create equitable obligations against the recipient of the property as follows. Note that they ALSO imply that YOU can use exactly the same mechanism against the government to impose obligations upon them, if they are trying to acquire your physical property, your services, your labor, your time, or impose any kind of obligation (Form #12.040) against you without your express written consent, because all such activities involve efforts to acquire what is usually PRIVATE, absolutely owned property that you can use to control the GOVERNMENT as the lawful owner:

“The State in such cases exercises no greater right than an individual may exercise over the use of his own property when leased or loaned to others. The conditions upon which the privilege shall be enjoyed being stated or implied in the legislation authorizing its grant, no right is, of course, impaired by their enforcement. The recipient of the privilege, in effect, stipulates to comply with the conditions. It matters not how limited the privilege conferred, its acceptance implies an assent to the regulation of its use and the compensation for it.”

[Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 (1876) ]The injustice (Form #05.050), sophistry, and deception (Form #05.014) underlying their welfare state system is that:

- Governments don't produce anything, but merely transfer wealth between otherwise private people (see Separation Between Public and Private, Form #12.025).

- The money they are paying you can never be more than what you paid them, and if it is, then they are abusing their taxing powers!

To lay, with one hand, the power of the government on the property of the citizen, and with the other to bestow it upon favored individuals to aid private enterprises and build up private fortunes, is none the less a robbery because it is done under the forms of law and is called taxation. This is not legislation. It is a decree under legislative forms.

Nor is it taxation. ‘A tax,’ says Webster’s Dictionary, ‘is a rate or sum of money assessed on the person or property of a citizen by government for the use of the nation or State.’ ‘Taxes are burdens or charges imposed by the Legislature upon persons or property to raise money for public purposes.’ Cooley, Const. Lim., 479.

Coulter, J., in Northern Liberties v. St. John’s Church, 13 Pa.St. 104 says, very forcibly, ‘I think the common mind has everywhere taken in the understanding that taxes are a public imposition, levied by authority of the government for the purposes of carrying on the government in all its machinery and operations—that they are imposed for a public purpose.’ See, also Pray v. Northern Liberties, 31 Pa.St. 69; Matter of Mayor of N.Y., 11 Johns., 77; Camden v. Allen, 2 Dutch., 398; Sharpless v. Mayor, supra; Hanson v. Vernon, 27 Ia., 47; Whiting v. Fond du Lac, supra.”

[Loan Association v. Topeka, 20 Wall. 655 (1874)]- If they try to pay you more than you paid them, they must make you into a public officer to do so to avoid the prohibition of the case above. In doing so, they in most cases must illegally establish a public office and in effect use "benefits" to criminally bribe you to illegally impersonate such an office. See The "Trade or Business" Scam, Form #05.001 for details.

- Paying you back what was originally your own money and NOTHING more is not a "benefit" or even a loan by them to you. If anything, it is a temporary loan by you to them! And its an unjust loan because they don't have to pay interest!

- Since you are the real lender, then you are the only real party who can make rules against them and not vice versa. See Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2 of the Constitution for where the ability to make those rules comes from.

- All franchises are contracts that require mutual consideration and mutual obligation to be enforceable. Since government isn't contractually obligated to provide the main consideration, which is "benefits" and isn't obligated to provide ANYTHING that is truly economically valuable beyond that, then the "contract" or "compact" is unenforceable against you and can impose no obligations on you based on mere equitable principals of contract law.

“We must conclude that a person covered by the Act has not such a right in benefit payments… This is not to say, however, that Congress may exercise its power to modify the statutory scheme free of all constitutional restraint.”

[Flemming v. Nestor, 363 U.S. 603 (1960) ]"... railroad benefits, like social security benefits, are not contractual and may be altered or even eliminated at any time."

[United States Railroad Retirement Board v. Fritz, 449 U.S. 166 (1980)]For further details on government franchises, see:

- Sovereignty Forms and Instructions Online, Form #10.014, Cites by Topic: "franchise"

- Government Franchises Course, Form #12.012

Slides

Video- Government Instituted Slavery Using Franchises, Form #05.030

For information on how to avoid franchises, quit them, or use your own PERSONAL franchises to DEFEND yourself against illegal government franchise administration or enforcement, usually against ineligible parties, see:

[SEDM Disclaimer, Section 4: Meaning of Words]

- Avoiding Traps on Government Forms Course, Form #12.023

- Path to Freedom, Form #09.015, Section 5

- Injury Defense Franchise and Agreement, Form #06.027

- SEDM Forms/Pubs page, Section 1.6: Avoiding Government Franchises

- The Government "Benefits" Scam, Form #05.040 (Member Subscription form)

- Why the Government is the Only Real Beneficiary of All Government Franchises, Form #05.051 (Member Subscription form)