Related Information:

- Sixteenth Amendment Authorities

- Sixteenth Amendment Never Lawfully Ratified

- Sovereignty Forms and Instructions Onine, Form #10.004, Cites by Topic: "income"

-

Great IRS Hoax

Great IRS Hoax

- Section 5.2.14.2: Sixteenth Amendment was proposed by President Taft as a tax on the NATIONAL government, not upon a geography

- Section 6.7.1 1925: William H. Taft's Certiorari Act of 1925

-

Sixteenth Amendment Congressional Debates-copy of entire Sixteenth

Amendment Congressional Debates, right from the Congressional Record

Sixteenth Amendment Congressional Debates-copy of entire Sixteenth

Amendment Congressional Debates, right from the Congressional Record - Great IRS Hoax-exhaustive analysis of the tax laws

-

Why Your

Government is Either a Thief or You Are a "Public Officer" for Income

Tax Purposes, Form #05.008 (OFFSITE LINK)-why income taxes only

apply to federal employees, contractors, and benefit recipients

Why Your

Government is Either a Thief or You Are a "Public Officer" for Income

Tax Purposes, Form #05.008 (OFFSITE LINK)-why income taxes only

apply to federal employees, contractors, and benefit recipients -

Flawed Tax Arguments to Avoid -flawed arguments you should avoid

in order to stay out of trouble. Among them is the claim that

the Sixteenth Amendment was never ratified in Section 1 of this document.

It's absolutely irrelevant to whether you owe taxes

Flawed Tax Arguments to Avoid -flawed arguments you should avoid

in order to stay out of trouble. Among them is the claim that

the Sixteenth Amendment was never ratified in Section 1 of this document.

It's absolutely irrelevant to whether you owe taxes

“It was not the purpose or effect of that amendment to bring any new subject within the taxing power.”

[Bowers v. Kerbaugh-Empire Co., 271 U.S. 170; 46 S.Ct. 449 (1926)]

Whenever there are controversies over the interpretation of a statute or a Constitutional provision, the first thing that courts of justice will resort to is the plain language of the law itself. If the language is unclear or subject to multiple interpretations, the courts will then examine the legislative intent revealed by those who wrote the law. The most revealing way to determine the legislative intent of any law is to examine the Congressional debates preceding its enactment. All changes to the law that were proposed during debate and rejected must then be rejected as not being consistent with the intent of the proposed law.

The first thing we must look at to discern the intent of the Sixteenth Amendment is the proposal of the President himself. The following written address was submitted to the U.S. Senate by President William H. Taft, in which he introduced the 16th Amendment and clearly revealed its legislative intent. It is very revealing, in that it shows that the intent was to allow the government to tax only its own employees but not private citizens. President Taft would also later be appointed to the Supreme Court in 1921 as the Chief Justice, and eventually became the only U.S. President who ever served as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and a Collector of Internal Revenue. He replaced E.B. White as the Chief Justice, who you may recall was the person who opposed the majority view in the Pollock Case that declared income taxes unconstitutional. White wanted to make direct taxes legal, and apparently, so did Taft. No other U.S. President, therefore, had a better understanding of the legal implications of the proposed 16th Amendment than did Taft.

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE - JUNE 16, 1909

[From Pages 3344 – 3345]

The Secretary read as follows:

To the Senate and House of Representatives:

It is the constitutional duty of the President from time to time to recommend to the consideration of Congress such measures, as he shall judge necessary and expedient. In my inaugural address, immediately preceding this present extraordinary session of Congress, I invited attention to the necessity for a revision of the tariff at this session, and stated the principles upon which I thought the revision should be affected. I referred to the then rapidly increasing deficit and pointed out the obligation on the part of the framers of the tariff bill to arrange the duty so as to secure an adequate income, and suggested that if it was not possible to do so by import duties, new kinds of taxation must be adopted, and among them I recommended a graduated inheritance tax as correct in principle and as certain and easy of collection.

The House of Representatives has adopted the suggestion, and has provided in the bill it passed for the collection of such a tax. In the Senate the action of its Finance Committee and the course of the debate indicate that it may not agree to this provision, and it is now proposed to make up the deficit by the imposition of a general income tax, in form and substance of almost exactly the same character as, that which in the case of Pollock v. Farmer’s Loan and Trust Company (157 U.S., 429) was held by the Supreme Court to be a direct tax, and therefore not within the power of the Federal Government to Impose unless apportioned among the several States according to population. [Emphasis added] This new proposal, which I did not discuss in my inaugural address or in my message at the opening of the present session, makes it appropriate for me to submit to the Congress certain additional recommendations.

Again, it is clear that by the enactment of the proposed law the Congress will not be bringing money into the Treasury to meet the present deficiency. The decision of the Supreme Court in the income-tax cases deprived the National Government of a power which, by reason of previous decisions of the court, it was generally supposed that government had. It is undoubtedly a power the National Government ought to have. It might be indispensable to the Nation’s life in great crises. Although I have not considered a constitutional amendment as necessary to the exercise of certain phases of this power, a mature consideration has satisfied me that an amendment is the only proper course for its establishment to its full extent.

I therefore recommend to the Congress that both Houses, by a two-thirds vote, shall propose an amendment to the Constitution conferring the power to levy an income tax upon the National Government without apportionment among the States in proportion to population.

This course is much to be preferred to the one proposed of reenacting a law once judicially declared to be unconstitutional. For the Congress to assume that the court will reverse itself, and to enact legislation on such an assumption, will not strengthen popular confidence in the stability of judicial construction of the Constitution. It is much wiser policy to accept the decision and remedy the defect by amendment in due and regular course.

Again, it is clear that by the enactment of the proposed law the Congress will not be bringing money into the Treasury to meet the present deficiency, but by putting on the statute book a law already there and never repealed will simply be suggesting to the executive officers of the Government their possible duty to invoke litigation.

If the court should maintain its former view, no tax would be collected at all. If it should ultimately reverse itself, still no taxes would have been collected until after protracted delay.

It is said the difficulty and delay in securing the approval of three-fourths of the States will destroy all chance of adopting the amendment. Of course, no one can speak with certainty upon this point, but I have become convinced that a great majority of the people of this country are in favor of investing the National Government with power to levy an income tax, and that they will secure the adoption of the amendment in the States, if proposed to them.

Second, the decision in the Pollock case left power in the National Government to levy an excise tax, which accomplishes the same purpose as a corporation income tax and is free from certain objections urged to the proposed income tax measure.

I therefore recommend an amendment to the tariff bill Imposing upon all corporations and joint stock companies for profit, except national banks (otherwise taxed), savings banks, and building and loan associations, an excise tax measured by 2 per cent on the net income of such corporations. This is an excise tax upon the privilege of doing business as an artificial entity and of freedom from a general partnership liability enjoyed by those who own the stock. [Emphasis added] I am informed that a 2 per cent tax of this character would bring into the Treasury of the United States not less than $25,000,000.

The decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Spreckels Sugar Refining Company against McClain (192 U.S., 397), seems clearly to establish the principle that such a tax as this is an excise tax upon privilege and not a direct tax on property, and is within the federal power without apportionment according to population. The tax on net income is preferable to one proportionate to a percentage of the gross receipts, because it is a tax upon success and not failure. It imposes a burden at the source of the income at a time when the corporation is well able to pay and when collection is easy.

Another merit of this tax is the federal supervision, which must be exercised in order to make the law effective over the annual accounts and business transactions of all corporations. While the faculty of assuming a corporate form has been of the utmost utility in the business world, it is also true that substantially all of the abuses and all of the evils which have aroused the public to the necessity of reform were made possible by the use of this very faculty. If now, by a perfectly legitimate and effective system of taxation, we are incidentally able to possess the Government and the stockholders and the public of the knowledge of the real business transactions and the gains and profits of every corporation in the country, we have made a long step toward that supervisory control of corporations which may prevent a further abuse of power.

I recommend, then, first, the adoption of a joint resolution by two-thirds of both Houses, proposing to the States an amendment to the Constitution granting to the Federal Government the right to levy and collect an income tax without apportionment among the several States according to population; and, second, the enactment, as part of the pending revenue measure, either as a substitute for, or in addition to, the inheritance tax, of an excise tax upon all corporations, measured by 2 percent of their net income.

Wm. H. Taft

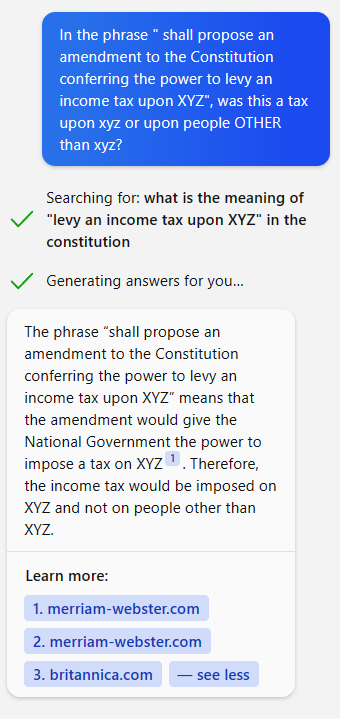

Some people have asserted that it is deceptive to claim that the phrase above " shall propose an amendment to the Constitution conferring the power to levy an income tax upon the National Government" implies it is a tax upon the government. In retort, it may interest the reader to know that:

- Taft could have said "shall propose an amendment to the Constitution conferring upon the national government the power to levy an income tax" but DID NOT state it more correctly this way.

- The legislative implementation of what he proposed he described as an excise and a privilege tax ONLY upon corporations, which even after the Sixteenth Amendment was ratified, is EXACTLY and ONLY what the Sixteenth Amendment currently authorizes. These coporations are NATIONAL corporations, not STATE corporations, by the way.

"Income" has been taken to mean the same thing as used in the Corporation Excise Tax Act of 1909, in the Sixteenth Amendment, and in the various revenue acts subsequently passed. Southern Pacific Co. v. Lowe, 247 U.S. 330, 335; Merchants' L. & T. Co. v. Smietanka, 255 U.S. 509, 219. After full consideration, this Court declared that income may be defined as gain derived from capital, from labor, or from both combined, including profit gained through sale or conversion of capital. Stratton's Independence v. Howbert, 231 U.S. 399, 415; Doyle v. Mitchell Brothers Co., 247 U.S. 179, 185; Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189, 207. And that definition has been adhered to and applied repeatedly. See, e.g., Merchants' L. & T. Co. v. Smietanka, supra; 518; Goodrich v. Edwards, 255 U.S. 527, 535; United States v. Phellis, 257 U.S. 156, 169; Miles v. Safe Deposit Co., 259 U.S. 247, 252-253; United States v. Supplee-Biddle Co., 265 U.S. 189, 194; Irwin v. Gavit, 268 U.S. 161, 167; Edwards v. Cuba Railroad, 268 U.S. 628, 633. In determining what constitutes income, substance rather than form is to be given controlling weight. Eisner v. Macomber, supra, 206. [271 U.S. 175]"

[Bowers v. Kerbaugh-Empire Co., 271 U.S. 170, 174, (1926)]

- The U.S. Supreme Court in Downes v. Bidwell agreed that the income tax extends wherever the GOVERNMENT extends, rather than where the GEOGRAPHY extends. Notice it says "without limitation as to place" and "places over which the GOVERNMENT extends".

"Loughborough v. Blake, 18 U.S. 317, 5 Wheat. 317, 5 L. Ed. 98, was an action of trespass (or, as appears by the original record, replevin) brought in the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia to try the right of Congress to impose a direct tax for general purposes on that District. 3 Stat. 216, c. 60, Fed. 17, 1815. It was insisted that Congress could act in a double capacity: in [****32] one as legislating [*260] for the States; in the other as a local legislature for the District of Columbia. In the latter character, it was admitted that the power of levying direct taxes might be exercised, but for District purposes only, as a state legislature might tax for state purposes; but that it could not legislate for the District under Art. I, sec. 8, giving to Congress the power "to lay and collect taxes, imposts and excises," which "shall be uniform throughout the United States," inasmuch as the District was no part of the United States. It was held that the grant of this power was a general one without limitation as to place, and consequently extended to all places over which the government extends; and that it extended to the District of Columbia as a constituent part of the United States. The fact that Art. I, sec. 20, declares that "representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States . . . according to their respective numbers," furnished a standard by which taxes were apportioned; but not to exempt any part of the country from their operation. "The words used do not mean, that direct taxes shall be imposed on States only which are [****33] represented, or shall be apportioned to representatives; but that direct taxation, in its application to States, shall be apportioned to numbers." That Art. I, sec. 9, P4, declaring that direct taxes shall be laid in proportion to the census, was applicable to the District of Columbia, "and will enable Congress to apportion on it its just and equal share of the burden, with the same accuracy as on the respective States. If the tax be laid in this proportion, it is within the very words of the restriction. It is a tax in proportion to the census or enumeration referred to." It was further held that the words of the ninth section did not "in terms require that the system of direct taxation, when resorted to, shall be extended to the territories, as the words of the second section require that it shall be extended to all the [**777] States. They therefore may, without violence, be understood to give a rule when the territories shall be taxed without imposing the necessity of taxing them."

- The definition of "person" in 26 U.S.C. §6671(b) and 26 U.S.C. §7343 for the purposes of penalty and criminal enforcement purposes limits itself to government employees and instrumentalities of the government. The rules of statutory construction and interpretation forbid adding anything to these definitions not expressly provided, such as PRIVATE constitutionally protected men and women. Thus, anyone who doesn't fall within the ambit of these definitions is, by definition, a VOLUNTEER because not a proper target of enforcement.

TITLE 26 > Subtitle F > CHAPTER 68 > Subchapter B > PART I >Sec. 6671

Sec. 6671. - Rules for application of assessable penalties

(b)Person defined

The term “person”, as used in this subchapter, includes an officer or employee of a corporation, or a member or employee of a partnership, who as such officer, employee, or member is under a duty to perform the act in respect of which the violation occurs.

TITLE 26 > Subtitle F > CHAPTER 75 > Subchapter D > Sec. 7343.

Sec. 7343. - Definition of term ''person''

The term ''person'' as used in this chapter [Chapter 75] includes an officer or employee of a corporation, or a member or employee of a partnership, who as such officer, employee, or member is under a duty to perform the act in respect of which the violation occurs

- The following memorandum of law proves that the only proper target of IRS enforcement are public officers WITHIN the government.

Why Your Government is either a Thief or You are a Public Officer for Income Tax Purposes, Form #05.007

https://sedm.org/Forms/05-MemLaw/WhyThiefOrPubOfficer.pdf - The fact that "United States" is geographically defined in 26 U.S.C. §7701(a)(9) and (a)(10) as the District of Columbia and the CONSTITUTIONAL states of the Union are never mentioned. That place is synonymous with the GOVERNMENT in 4 U.S.C. §72 and not any geography.

- The fact that the ACTIVITY that is subject to excise taxation within the Internal Revenue Code is legally defined in 26 U.S.C. §7701(a)(26) as "the functions of a public office", meaning an office WITHIN the national and not state government. For exhaustive details on this subject, see:

The "Trade or Business" Scam, Form #05.001

https://sedm.org/Forms/05-MemLaw/TradeOrBusScam.pdf - The fact that the Federal Register Act and the Administrative Procedures act both limit the TARGET of direct STATUTORY enforcement to the following groups, none of which include most people in states of the Union and which primarily consist of government employees only::

8.1 A military or foreign affairs function of the United States. 5 U.S.C. §553(a)(1).

8.2 A matter relating to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts. 5 U.S.C. §553(a)(2).

8.3 Federal agencies or persons in their capacity as officers, agents, or employees thereof. 44 U.S.C. §1505(a)(1).

You can find more on the above in:

Challenge to Income Tax Enforcement Authority Within Constitutional States of the Union, Form #05.052

https://sedm.org/Forms/05-Memlaw/ChallengeToIRSEnforcementAuth.pdf

- The fact that they can only tax legislatively created offices who work for them. See:

Hierarchy of Sovereignty: The Power to Create is the Power to Tax, Family Guardian Fellowship

https://famguardian.org/Subjects/Taxes/Remedies/PowerToCreate.htm

- The idea that governments are created to PROTECT private property, not steal it, and that taxation involves the institutionalized process of converting PRIVATE property to PUBLIC property without the express consent of the owner. Thus, the process of PAYING for government protection involves the OPPOSITE purpose for which governments are created—converting PRIVATE property to PUBLIC property, often without the consent of the owner, for the purposes of delivering the OPPOSITE, which is PREVENTING PRIVATE property from being converted to PUBLIC property! The Declaration of Independence declares that all just powers derive from the consent of the governed, and yet we make an EXCEPTION to that requirement when it comes to taxation? Absurd. So they HAVE to procure your consent to occupy a civil statutory office BEFORE they can enforce against you or else they are violating the Thirteenth Amendment and engaging in criminal human trafficking. For a description of just how absurd it is to NOT require consent to this office and to convert (STEAL) private property without the consent of the owner, see:

Separation Between Public and Private Course, Form #12.025

https://sedm.org/LibertyU/SeparatingPublicPrivate.pdf - A query of the ChatGPT-4 AI Chatbot confirms our analysis is correct:

So what the President proposed was an excise tax on public offices within the government itself, and nothing more. This is important. You can view the original version of Taft’s speech above along with the complete Congressional Debates on the Sixteenth Amendment on our website at the address below:

After we look at what our President proposed, the next thing we must look at to discern legislative intent are the Congressional debates on the Sixteenth Amendment in 1909. Three different written versions of the Sixteenth Amendment were proposed before the one we have now was approved by Congress and sent to the states for ratification. Below is a summary of each in written form:

Table 3-2: Versions of Proposed Sixteenth Amendment prior to approval

| Version | Text of proposed Amendment | Vote on proposed amendment |

| Senate Joint Resolution (S.J.R.) No. 25 | “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes and inheritances.” | Rejected |

| Senate Joint Resolution (S.J.R.) No. 39 | “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect direct [emphasis mine] taxes on incomes without apportionment among the several States according to population.” [44 Cong.Rec. 3377 (1909)] | Rejected |

| Senate Joint Resolution (S.J.R.) No. 40 | “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.” [This is the version of the Sixteenth Amendment we have now] | Approved 77 to 15 on July 5, 1909. |

The first two, obviously, were voted down, but what were they? Both versions that were voted down included proposals to levy a direct tax on the states without apportionment and one of them proposed to eliminate the apportionment requirements found in Article 1, Section 9, Clause 4 and Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution!

Senator Brown from Nebraska wrote all three versions of the Sixteenth Amendment that were voted on by Congress, which included S.J.R. No. 25, S.J.R. No. 39, and S.J.R. No. 40, in that order. S.J.R. No. 40 was the one finally approved. The Senate voted in favor of the 16th Amendment we have now (S.J.R. No. 40) at 1 o’clock on July 5, 1909. Senator Aldrich had earlier tried to ram it through the Senate on Saturday, July 3rd, a holiday weekend, for an immediate vote without debate when only 52 senators were present. A few senators protested and the vote was set for the following Monday. As a result of the minimal debate that did take place on July 3rd, several amendments were proposed to S.J.R. No. 40 that came up for a vote at the appointed hour of 1 P.M. Monday, July 5th.

The first of these was an amendment to S.J.R. No. 40, proposed as S.J.R. No. 25 by Senator Bailey of Texas to provide that conventions of each of the several States be required to ratify the constitutional amendment as opposed to the state legislatures. This was voted down.

Next was the second amendment to the proposed Sixteenth Amendment in the form of S.J.R. No. 39. This amendment by Bailey to add the language “and may grade the same” to modify the term “income tax” as a way to provide that the tax may be graduated. Bailey proposed this language on Saturday, July 3rd. By Monday, July 5th, when this came up for a vote, Bailey realized it would fail and tried to have it withdrawn. Bailey wanted it withdrawn because, according to Bailey:

“Mr. President, I am satisfied that this amendment will be voted down; and voting it down would warrant the Supreme Court in hereafter saying that a proposition to authorize Congress to levy a graduated income tax was rejected.” [44 Cong.Rec. 4120 (1920)]

In other words, Senator Bailey understood that once Congress rejected a particular provision while amending the Constitution, Congress would be forever barred from implementing that provision by way of statute in the future. This legal principle applies to all legislation, even to income taxes. It is also why the Framers had the Constitution mandate that Congress keep a journal.

Bailey was told by the Senate’s Vice President that he could not withdraw the amendment and that it must be voted on. The rules required it. Senator Aldrich intervened and somehow the rules were suspended and the amendment was withdrawn without a vote.

Next was an amendment by Senator McLaurin of Mississippi. His proposed amendment to S.J.R. No. 40 was as follows:

“The SECRETARY. Amend the joint resolution by striking out all after line 7 and inserting the following: ‘The words ‘and direct taxes’ in clause 3, section 2, Article I, and the words “or other direct,’ in clause 4, section 9, Article I. Of the Constitution of the United States are hereby stricken out.” [44 Cong.Rec. 4109 (1909)]

Senator McLaurin’s amendment would have stricken out the requirement for apportionment of direct taxes from Article 1, Section 9, Clause 4 and Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution and made the income tax into an unapportioned direct tax! The Senate rejected this, as this amendment failed by voice vote. Had this amendment passed, it would have provided authority for a species of income tax that was inherently a direct tax to be levied without apportionment, and it would have changed the original wording of the Constitution to forever do away with the prohibition against direct taxes.

Lastly, there was an amendment by Senator Bristow of Kansas to replace S.J.R. No. 40 with S.J.R. No. 39. S.J.R. No. 39 read:

“The Congress shall have the power to lay and collect direct[emphasis mine] taxes on income without apportionment among the several States according to population.”

This substitute amendment also included a provision to elect senators by popular vote. After some debate this was also rejected by voice vote.

Next, S.J.R. No. 40, the version of the Sixteenth Amendment that we have now, was voted on and passed 77 to 15. So what can we conclude from all of this? Well, first of all we can conclude that the Senate understood it was the practice of the Supreme Court at the proceedings of Congress to see what the intent of the Congress was. If Congress voted on a measure and rejected it, then the Supreme Court would interpret that vote as a clarification of the intent and purpose of Congress. Here is how Sutherland’s rules on statutory construction explains it:

“One of the most readily available extrinsic aids to the interpretation of statutes is the action of the legislature on amendments which are proposed to be made during the course of consideration in the legislature. Both the state and federal courts will refer to proposed changes in a bill in order to interpret the statute as finally enacted. The journals of the legislature are the usual source for this information. Generally the rejection of an amendment indicates that the legislature does not intend the bill to include the provisions embodied in the rejected amendment.” [Sutherland on Statutory Construction, sec. 48.18 (5th Edition)]

We also learned that twice the Senate was offered the opportunity to vote on a measure to provide that the income tax being considered by the 16th Amendment would provide for a direct tax within the constitutional meaning of the term “direct tax.” Twice in the hour or so prior to the final Senate vote on the income tax amendment, the Senate rejected the opportunity to bring direct taxes within the scope of the 16th Amendment. This issue was squarely before the Congress, and Congress rejected it.

“It is plain, then, that Congress had this question presented to its attention in a most precise form. It has the issue clearly drawn. The first alternative was rejected. All difficulties of construction vanish if we are wiling to give to the words, deliberately adopted, their natural meaning.”

[U.S. v. Pfitsch, 256 U.S. 547, 552 (1921)]

“When a court reviews an agency’s construction of the statute which it administers, it is confronted with two questions. First, always, is the question whether Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue. If the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter; for the court, as well as the agency, must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of the Congress.”

[Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984)]

Now of these two opportunities to include direct taxes within the authority of the 16th Amendment, the second of the two also included a provision on the election of Senators by popular vote. But the same issue of the election of Senators was later approved by the Senate and sent out to the several States as the 17th Amendment to the Constitution. This Amendment was purportedly ratified and is not part of our Constitution. Therefore, the reason the second Bristow amendment failed was due to the term “direct taxes” and not because of the election of senators issue.

It can’t be any more clear. The 16th Amendment does not provide authority for a direct tax on incomes, but only authority for an indirect tax on incomes. A direct tax on incomes is a tax that diminishes the source of the income. An indirect tax on income is a tax on unearned income or profit; such a tax leaves the source of the income undiminished. Twice during the debates on the 16th Amendment (S.J.R. No. 25 and S.J.R. No. 39), Congress rejected the idea of bringing direct taxes within the authority of the 16th Amendment. Then twice more, on July 5, 1909, Congress rejected the idea by direct vote of the Senate. Despite this congressional hostility to the idea, the IRS and the lower courts admit they are collecting a direct tax. At a minimum this is scandalous. In reality it is probably criminal.

"Acts of Congress are to be construed and applied in Harmony with and not to thwart the purpose of the Constitution.”

[Phelps v. U.S., 274 U.S. 341, 344 (1927)]

“Courts should construe laws in Harmony with the legislative intent and seek to carry out legislative purpose. With respect to the tax provisions under consideration, there is no uncertainty as to the legislative purpose to tax post-1913 corporate earnings. We must not give effect to any contrivance which would defeat a tax Congress plainly intended to impose.”

[Foster v. U.S., 303 U.S. 118, 120-1 (1938)]

Today the government’s story is that the 16th Amendment provides authority for an unapportioned direct tax. But in 1916 the Attorney General of the United States’ office understood this differently. In the case of Peck & Co. v. Lowe the attorney general for the United States stated:

"It is, however, equally clear that a general income tax is an excise tax laid upon persons or corporations with respect to their income: that is, a person or a corporation is selected out from the mass of the community by reason of the income possessed by him or it...

"This is brought out clearly by this court in Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad Co., 240 U.S. 1, and Stanton v. Baltic Mining Co., 240 U.S. 103. In the former case it was pointed out that the all-embracing power of taxation conferred upon Congress by the Constitution included two great classes, one indirect taxes or excises, and the other direct taxes, and that of apportionment with regard to direct taxes. It was held that the income tax in its nature is an excise; that is, it is a tax upon a person measured by his income...It was further held that the effect of the Sixteenth Amendment was not to change the nature of this tax or to take it out of the class of excises to which it belonged, but merely to make it impossible by any sort of reasoning thereafter to treat it as a direct tax because of the sources from which the income was derived."

[Brief for the United States at 14-15 in Peck & Co. v. Lowe, 247 U.S. 165 (1917). Not in the ruling itself]

This argument by the United States was in response to the question put to the court by Peck & Co. as to whether the 16th Amendment created any new taxing power.

“The Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution has not enlarged the taxing power of Congress or affected the prohibition against its burdening exports.”

[Brief for the Appellant at 11, Peck & Co. v. Lowe, 247 U.S. 165 (1917)]

Had the 16th Amendment provided for an unapportioned direct tax this would have been an enlargement of the taxing power of Congress. At least on the issue of whether there was an exemption to the apportionment rule for direct taxes, all parties to the Peck & Co. v. Lowe Case agreed there wasn’t. The issue of the case dealt with the taxation of export, not direct taxes. The Supreme Court ruled in Stanton v. Baltic Mining that there was no enlargement to the taxation authority of Congress by the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment. Therefore it is settled; the 16th Amendment did not grant to Congress an exception to the apportionment rule for direct taxes required by the Constitution.

Just as the intent of the Congress should be followed when constructing a statute, so must the intent of the People, in their sovereign capacity, be followed when construing an amendment to the Constitution.

The construction of the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution absolutely proves our argument. It was necessary for the 21st Amendment to repeal the 18th Amendment before the 21st Amendment could have any effect. Both Amendments related to “intoxicating liquors.” The 18th Amendment prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation or importation and use of them. Section 1 of the 21st Amendment reads “The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.” The 21st Amendment would not have been in Harmony with the totality of the Constitution unless the 18th Amendment was first repealed. Similarly, had it been the intention of Congress to offer to the people an income tax amendment which would give Congress the power to impose a direct tax on the source of income without apportionment, the 16th Amendment would have provided for such power only by modifying the direct taxing clauses of the Constitution found at Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 and Article 1, Section 9, Clause 4. The 16th Amendment did not do this.

Section 2 of the 18th Amendment included an enforcement clause which read “The Congress and the several States shall have the concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” The 21st Amendment did not include such an enforcement clause as the 21st Amendment was not conveying a new power to Congress, but in fact was adding a limitation on the power of Congress. Nor does the 16th Amendment have an enforcement clause, as it does not convey a new power to Congress, but only clarifies a theory of taxation. That theory was the basis for the Pollock Decision. The Pollock Decision was overturned by the 16th Amendment.

Congress did not modify the direct taxation clauses of the Constitution by the construction of the 16th Amendment. Therefore, the 16th Amendment does not provide authority for a direct tax on sources of income which enjoy constitutional protection. (Some sources of income do not enjoy constitutional protection, like income derived from sources without (outside) the several States of the Union.) Therefore, there is no authority for Congress to tax one of the several States of the Union, unless that tax is apportioned.[1]

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Congress could by statute define the earned income of an elected or appointed government employee to be “wages.” Then Congress could levy an income tax on these “wages” as this would be a tax on a privilege; the privilege being employment by the federal government. Such a tax is entirely constitutional.